Stress and tension spreads contagiously and chronically through our relationship networks, therefore holistic psychological health and well-being requires integrating solo self-care practices with an understanding of our social brain and maturing our social nervous system.

Part 1 of a 4-Part Series: Meet the Social Nervous System. Click here to read part 2.

Our brain is intrinsically a social brain.

While we know instinctively that our relationships influence how we react, think and feel, it is only with recent advances in neuroscience that we can begin to observe and understand just how fundamentally our social encounters are intertwined with our individual experiences in the development and ongoing activity of our brain. From our earliest encounters and throughout our lives, our relationships with others constantly shape, influence and direct our perception of, and engagement with the world around us.

This shift, from a solo view of our functioning, where we think and act individually, to a social perspective, where our mind’s activity is also forged through relational dynamics has a fundamental impact on how we understand the journey towards psychological health and well-being. We cannot simply focus on individual self-care practices, for holistic health we also need to develop the quality of our relational interactions. Our well-being is embedded in relationship.

We are far more familiar thinking about our brain as a solo, solitary brain than we are thinking about it as a social brain. Our bias towards thinking about our functioning as distinct, individual and separate from others is particularly visible when we consider our approach to understanding and tackling stress.

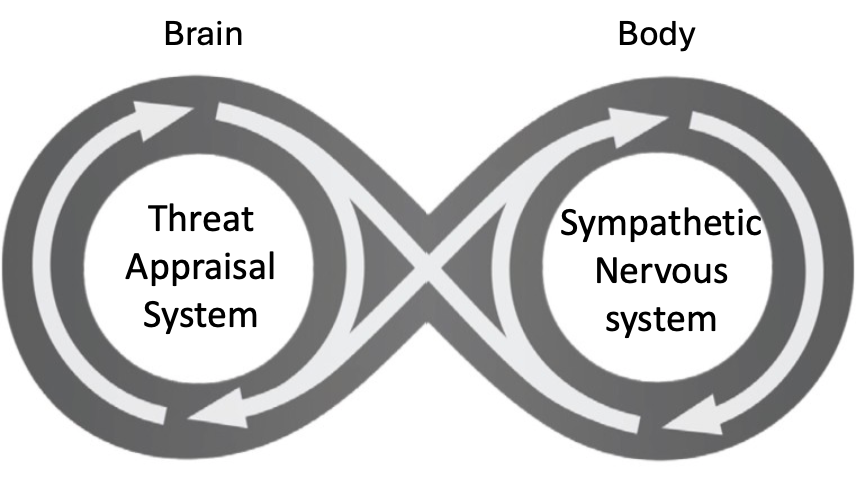

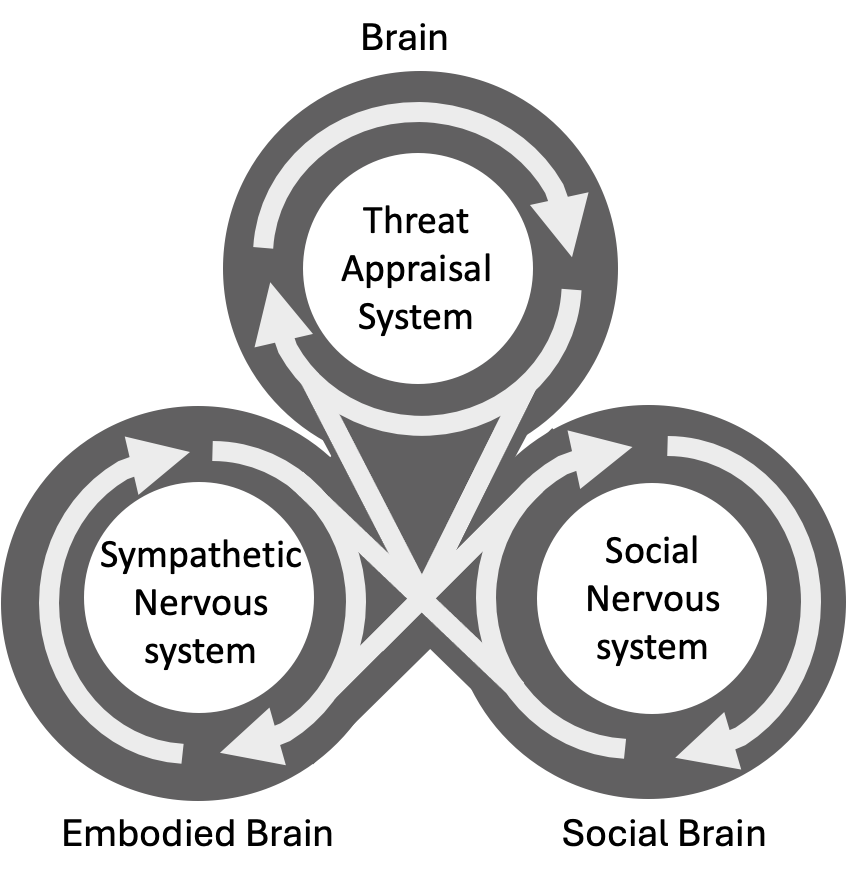

We focus on our personal experience of stress within our brain and body. How our brain acts as a threat appraisal system, analysing sensory information to determine potential danger, but how it can sabotage us by automatically reacting to everyday stressors in the same way it instinctively reacts to life or death threats. How detection of threat then activates our embodied nervous system, specifically our sympathetic nervous system, the network of nerves connecting brain and body, which drives adrenaline driven stress reaction.

We consider the benefits of stress to drive individual survival and problem solving. That this automatic reactivity primes our body for survival action via fight, flight or freeze behaviours and how it also produces eustress, the positive energy, focus and drive that is necessary to tackle the challenges we face in everyday life.

We also focus on the detrimental impact of stress to our individual mind and body. How constant adrenaline production together with stress hormone, cortisol leads to distress and burnout. [The Understand the Stress Cycle blog unpacks this in more detail).

Focusing on stress as an individual experience results in stress management and well-being techniques that are primarily a solo pursuit. Cultivating healthy self-care habits, engaging in exercise, embracing mindfulness and incorporating breath work all focus on the personal self-regulation of our mind and body. They focus on ‘tapping out’ the excess adrenaline flooding our body and regulating our sympathetic nervous system so that we reach a place of calm again.

While this understanding of stress is accurate, and such embodied self-care practices are vital to our health and wellbeing, they only tell half the story. To understand the whole story, we need to incorporate an understanding of how relationships (and the stress they transmit) simultaneously impact our brain and body. We need to integrate our social brain.

When we consider the origin of our individual stress response we are often invited to journey back to our ancestors. The development of our instinctive fight or flight adrenaline reaction is explained as an evolutionary survival mechanism for “Colin the Caveman” as he faced the dangers of sabre-tooth tigers and wildfires. However, the reality is that from the earliest homo sapiens, survival was never an individual discipline, it was always a team sport. For one to survive, the tribe needed to survive.

The development of our social brain, the capacity for us to understand social cues as communication tools, allowed us to thrive as well as survive together. The development of our social engagement system meant that during times of stability and safety we thrived together by sharing responsibilities, resources, ideas and raising the next generation. And during times of threat, danger and uncertainty, we survived together, our Social Nervous System (the term Dr Kissell has given to our relational survival system) [link to How the SoNS is toxic for wellbeing] enabling us to sense fear and escape as if with one mind, or as we call it, with our Team Brain® [link to Meet the team brain blog].

To that end a social brain understanding of our stress reaction requires us to focus more on the herd of wildebeest also escaping the sabre-toothed tiger than on Colin the Solo Survivalist. Antelope do not act individually when facing threat, each reliant upon their own brain and body for survival. Instead, to escape a prowling predator, only one member of the herd needs to detect the tiger’s presence. The moment one antelope spots the threat and pricks up their ears in alarm, the whole group feel the change and sense the tension. This automatic and instinctive collective stress reaction allows the herd to feel the fear in unison, and gallop away in together.

The same collective communication occurs between humans via our social brain. Just like the antelope, we are all finely attuned to detecting fear and tension in others. When one member of the tribe spots danger and feels the fear, their automatic non-verbal cues result in an almost instantaneous experience of dread across the whole group, every member experiencing the same adrenaline fuelled physiological reaction, as if they had all seen the danger for themselves.

In survival scenarios this rush of collective adrenaline is highly effective, priming the group to react fast and escape together. But in today’s pressured, urgent and complex world, when another’s stress is rarely due to an immediate threat to life, our sensitivity to tension in others is a burden that burns us out.

As we integrate our social brain into our consideration of health and well-being we can begin to understand why our individual, solo well-being approaches are often ineffective. We might be taking full responsibility for our own mental health, but if we end our HeadSpace meditation and immediately receive an irate text from our partner complaining about their useless parent, or join a meeting with our stressed out boss panicking about their own workload, we catch their stress and find ourselves submerged in adrenaline fuelled anxiety and pressure once again.

A holistic, social brain approach to well-being recognises that stress and pressure come from our interactions with others as much as from our own senses, therefore long-term well-being relies on us learning to regulate the arousal of our shared, social nervous system as effectively as we seek to regulate our individual, embodied sympathetic nervous system.