Stress is essential, but too much harms health. Understand the stress response, learn the stages of the stress cycle, discover how stalled stress cycle impacts health, and when stress has become THE problem.

Part 1 of a 2-Part Series: Understanding the Stress Cycle and How to Reduce Stress. Click here to read part 2.

While we might not like it, stress is a fundamental aspect of our existence. In fact, we need it for our survival in the world.

Whenever we face a new, unknown situation; meet a problem that is difficult, or face a dangerous, life threatening scenario, it is stress that ensures we proactively tackle the challenge facing us. It focuses our attention, enhances problem solving, drives decision making and unlocks energy for action.

But when our stress level rises too high or stays elevated for too long, it’s impact becomes counterproductive. Our body enters a constant in a state of alert: tense, agitated, anxious and panicked. Our brain activity becomes restless, unfocused, preoccupied and ruminating. We do not make good decisions. We cannot focus on the task at hand. We move from being thoughtfully proactive to being instinctively reactive.

These symptoms are the natural and normal side effects of our body’s ongoing attempt to survive perceived threat. But if we do not recognise this predictable consequence and take efforts to regulate our stress and recalibrate, then stress ceases to be our survival problem solver and becomes THE problem. All our focus shifts towards alleviating this overwhelming inner experiences.

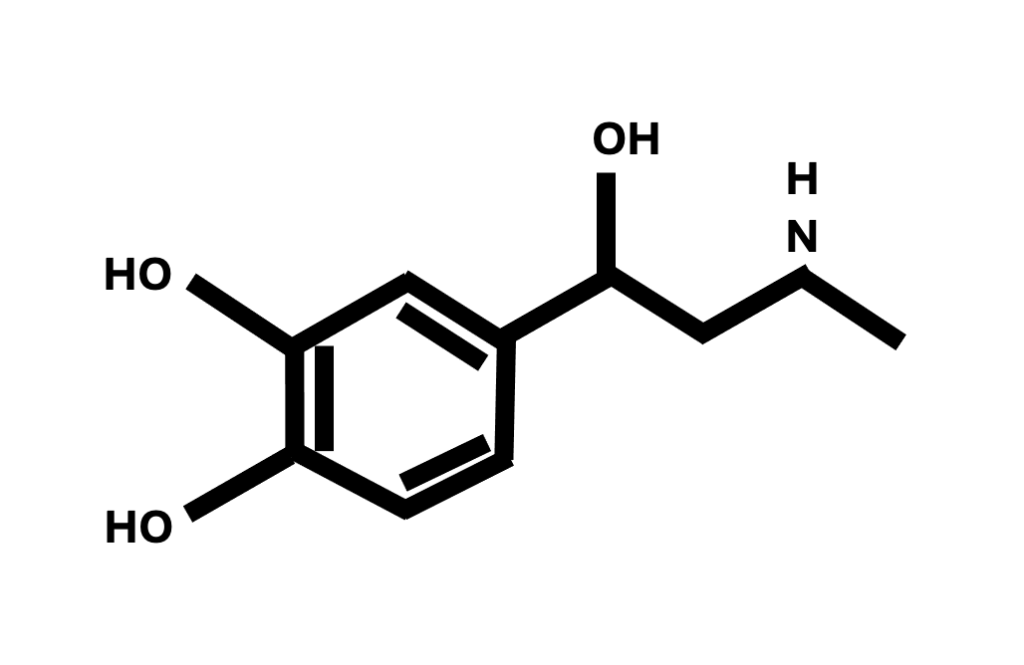

For all it’s gigantic impact, stress is actually the impact of a little hormone and neurotransmitter called adrenaline.

Our brain detects threat via the amygdala, an almond-shaped structure located close to the centre of the brain. Once activated, it almost instantaneously directs our adrenal glands to produce adrenaline (also known as epinephrine). As adrenaline floods our body it triggers automatic physiological changes which prepare us to react quickly to the new, difficult or dangerous and create our instinctive fight, flight and freeze reactions.

This adrenaline neural superhighway prioritises speed over nuance, and to do that, it takes a generalised approach to threat. Anything that seems in the least bit dangerous can prompt a fight, flight or freeze response. Whether the fear or pressure is large or small, real or imagined, current or future, environmental or relational, explicit or implicit, short-term or long-term, our body’s reaction is to unleash adrenaline.

Adrenaline is our first line of defence when facing danger. However, if the situation cannot be resolved promptly, another stress hormone, cortisol, is also released. Cortisol allows us to sustain our alertness and energy supply to tackle longer term challenges. The impact of cortisol will be unpacked in depth in a future blog.

The four stages of the stress cycle capture the way our body is designed to use adrenaline.

1. Neutral

The cycle starts at neutral, when we have no external threats or fears. At this point our body is attending to the everyday processes of our “internal” or physiological survival. The parasympathetic branch of our autonomic nervous system ensures our basic bodily functions like heartbeat, blood flow and digestion are stable, healthy and in balance. At this point we are calmly responsive to our environment.

2. Threat perceived

The moment threat is perceived then the sympathetic branch of our nervous system takes over, switching focus to our “external” survival and prompting the release of adrenaline. Within milliseconds the body is primed for action as energy reserves are unlocked, heart rate increases and oxygen intake is maximised. Simultaneously our mind’s capacity for problem solving is enhanced as adrenaline increases alertness, focus and arousal.

3. Threat tackled

Adrenaline produces a singled minded focus on survival. The hormone driving rapid decision making and the concurrent build up of energy enables us to proactively tackle the challenge we face. Our concentration on the task at hand is so intense that we rarely even notice adrenaline’s physical impact.

4. Threat over

Once the threat is addressed and survival assured, then adrenaline is no longer needed. Production ceases, the hormone is broken down by enzymes in the body and the side-effects dissipate. The stress cycle is completed, the parasympathetic nervous system switches back on and the body recalibrates to its relaxed neutral baseline state.

If the natural stress cycle stalls and does not complete the circuit back to neutral then we start to experience the negative consequences of stress.

Without a recalibration to baseline adrenaline production continues unabated. It begins to overwhelm our body and we become stuck in a heightened state of threat and alert. We start to notice the unpleasant tension adrenaline causes across our body, the butterflies in our stomach, the shortness of breath, thumping heart, tingling or trembling, sweating, dry mouth and feeling jittery. Our brain functions are similarly impacted and we experience adrenaline fulled over-thinking, rumination and tunnel vision.

At this point the physical impact of adrenaline becomes so dominant that surviving this internal threat can become our primary goal. We lose sight of the original external threat which prompted these symptoms in the first place and our concentration shifts to managing these distressing physical and mental side effects.

Unharnessed adrenaline is the key factor in an array of mental health, relationship and neurodiversity challenges. We call this excessive adrenaline production stress, but we might also name it anxiety, pressure, irritation or tension. It underpins anxiety disorders, from panic attacks to social anxiety and generalised anxiety disorder as well as fuelling anger, aggression and violence in relationships and being the root cause of autistic meltdown and shutdown.

Read the next blog in the series discover the five reasons for a stalled stress cycle, the consequences of chronic stress, and the four skills that help complete the stress cycle and lower your stress levels for the long-term